Just a pearl necklace

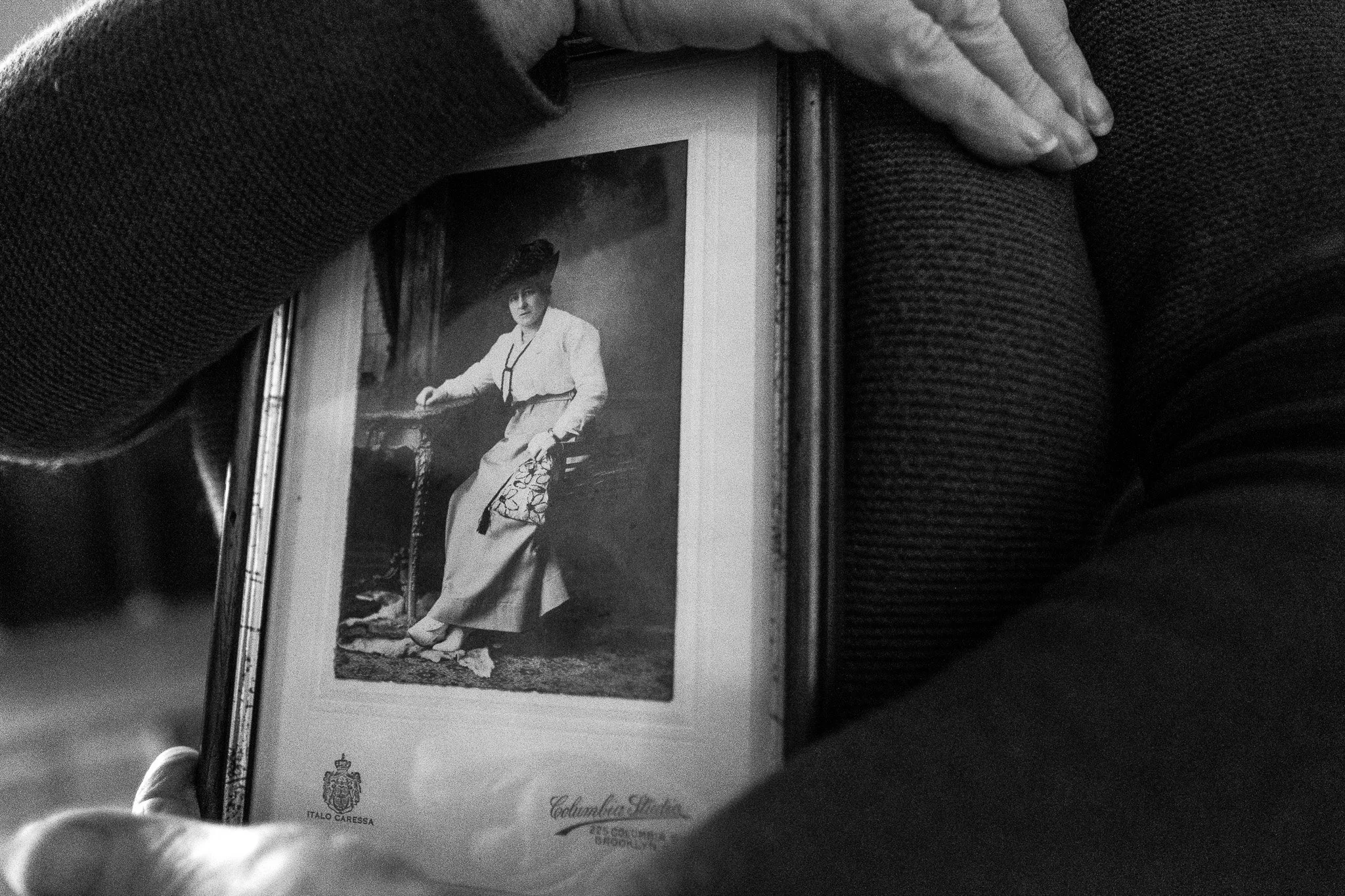

A pearl necklace, white gloves made of the finest leather, a gramophone, and a rich collection of vinyl records. These are the only mementos that Anna, my grandmother, brought with her in 1929 when she returned to Italy from New York, where she was born, at the age of just 8.

Between 1880 and 1915, over 4 million Italians arrived in the United States, out of approximately 9 million migrants who chose to cross the ocean to the Americas. They left from Genoa, but also from Le Havre, France. These were the decades following the unification of Italy, during the so-called “great emigration” (1876-1915). My great-grandfather, Paolo Mazzei, left from Le Havre in 1906. The journey was less expensive from France. He had a third-class ticket in his pocket, like most of the people on board, more than a thousand migrants. He wanted to go to California, the ‘New Frontier’, i.e. the West, which offered more opportunities.

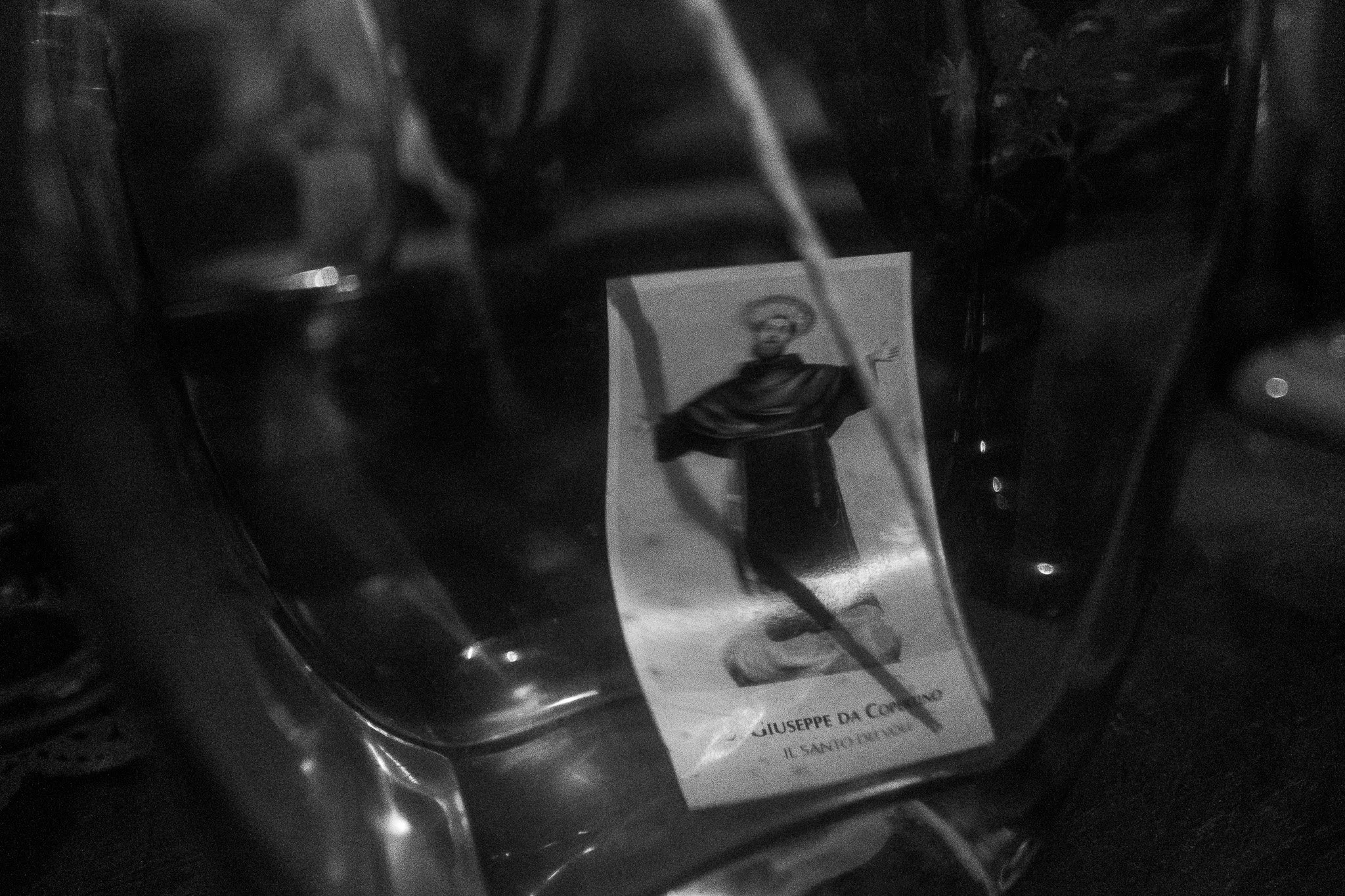

Paolo was a carpenter from Vernole, a village not far from the Adriatic coast of the Salento peninsula. Work had been scarce for some time, there was no money, and the dream of “Merica,” already a reality for many of his compatriots, seemed the only alternative to a life of hardship

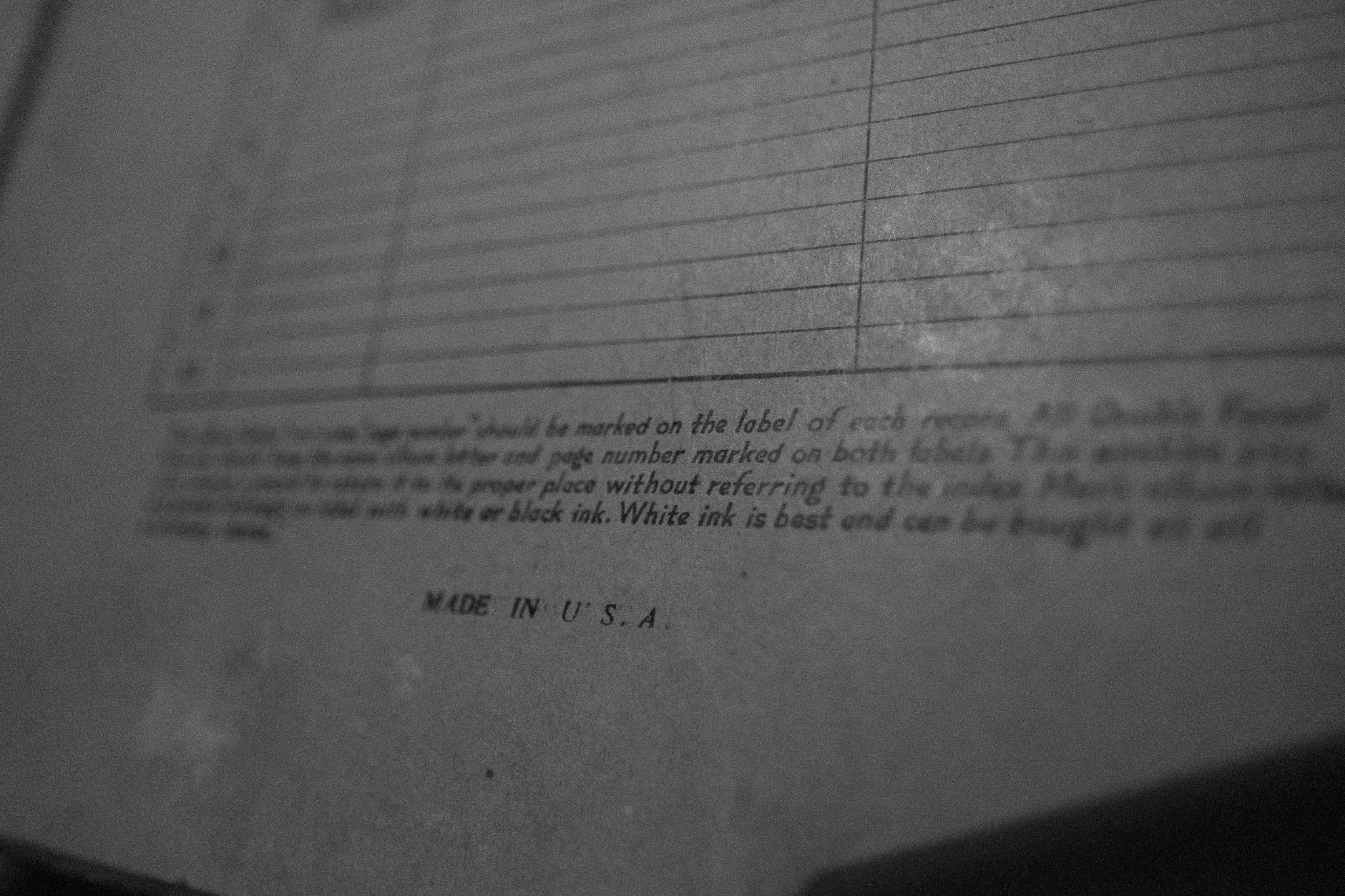

Upon arrival in New York, he disembarks at Ellis Island: the gateway to the New World was an artificial island built with debris from the excavation of the New York subway. A series of rigorous checks await him. The selection process is drastic: people are rejected for illness, extreme poverty, being too young or too old, or marital status (women and orphans without support in the new country). With his suitcase in hand and his gait still uncertain after the long sea voyage, he approached the immigration desk. They asked him for his personal details, his profession, his destination, his financial resources, and any criminal convictions. And, last but not least, his political orientation. In a few hours, at a wooden desk, the fate of a man or entire families was decided.

As time passed, the selection process became tougher. In 1917, the Literacy Act was passed, a law on illiteracy that imposed restrictions on immigration and affected many Italians, especially those from the south. Further restrictions were introduced in 1921 and 1924, with laws establishing the annual number of immigrants. My great-grandfather manages to get through. He is in good health, has a job, and can read and write. However, he will soon have to change his plans. No California. Paolo meets his future wife in Little Italy, the Italian neighborhood in New York. Lucia is from a town near Vernole, Monteroni. He finds a job in the shipyards, while she, a skilled seamstress, is the head of a clothing factory. Their first and only daughter, Anna, is born in Brooklyn on April 26, 1921. The Mazzei family lives in Brooklyn until, for reasons unknown, Paolo decides to return to Italy. My grandmother always regretted not staying in America. Joking one day, I told her that perhaps it was not her destiny. If she had stayed in New York, my father would not have been born, and therefore neither would I, who bears his name. She smiled at me without answering.